Training: Introduction to Citizen Science: scope, methodology, tools and practices

As part of UCL’s commitment to training and upskilling HEI staff and students and members of the public, we ran this short 30 minute webinar prior to all our O3 roundtables with community members as an optional extra event, which roundtable participants could attend or not as they chose. We also ran it on 14th September.

This webinar was run by Alice Sheppard, UCL’s Community Manager. It took the form of a short talk with room for questions, though it was mainly intended to spark discussion about whether – and, if so, how – citizen science could benefit the community or voluntary organisations to which the roundtable participants often belonged.

The talk took 4 parts:

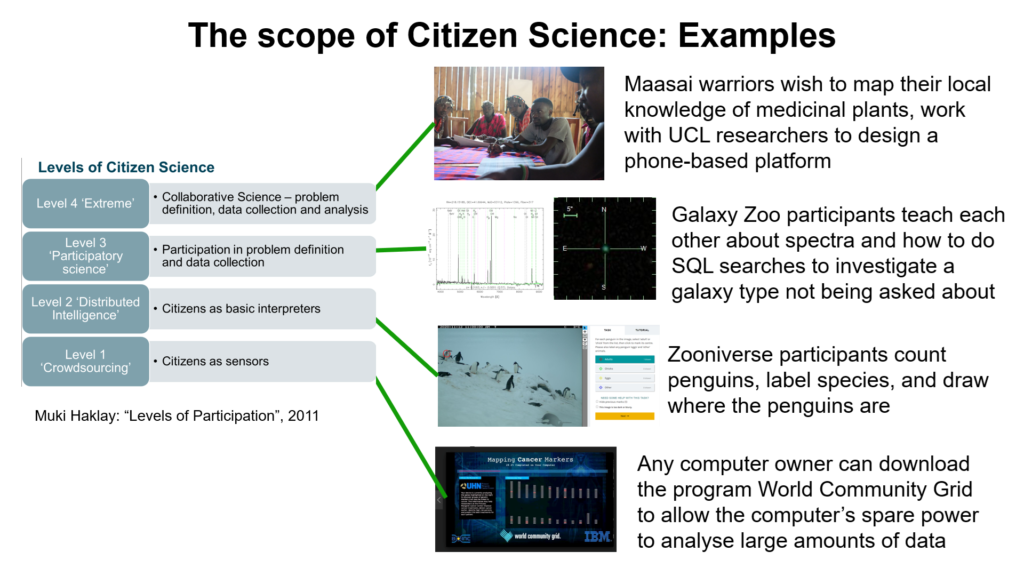

- Scope: For this, Alice showed several wide-ranging examples of citizen science projects, such as Project Budburst where plant life cycles are recorded, Galaxy Zoo where images of the Universe are clicked on to categorise, Extreme Citizen Science where indigenous people work with UCL anthropologists to record environmental intrusions or their local knowledge, or FoldIt in which participants “play a game” to create 3D maps of proteins. We also took a look at Muki Haklay’s “levels of participation”, applying these levels to examples of projects.

As part of considering the scope, it is worth noting that citizen science need not be especially “scientific” – it can mean, for example, recording buildings or areas of a city that are inaccessible to some people, or asking for people’s opinions or experiences in order to produce a useful map or tool.

- Tools: When collecting and analysing data for a citizen science project, what do you need? The most common answer is simply your smartphone or your laptop, where you’ll be shown an image and asked a question about it, or where you use your phone to take a picture or record levels of noise and light, for example. However, other tools may be useful – very basic items such as hand lenses and butterfly nets for biodiversity sampling, or lab tools or substrates to run tests such as for pollution identifying chemicals. In some cases, major tools are required such as space telescopes – in this case, the project will obviously be run by professional scientists working as a large team, and the telescope in question be shared among many!Tools are not just used for data gathering, but to create and run the project. A tool might include a website, which might be a platform such as Zooniverse or SciStarter, on which you gather your data and communicate with participants. Alice also mentioned flip-charts, as these are quick and eye-catching to passers-by, and have been used in some public projects such as BioBlitzes and gadget repair parties, not only to record but also to recruit more participants.

- Practices and Methodologies: These are nearly the same thing, so they were addressed together. A practice is a common technique or process used to complete a scientific task; a methodology, in this context, is when a practice becomes formalised enough to have a name that is widely used in the field. Two examples are HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) and FPIC (Free, Prior and Informed Consent). If you are running a citizen science project, you will probably use several different practices and methodologies at different stages of your project. There is never a single one-size-fits-all approach.

Because this talk was mostly aimed and voluntary and community groups, Alice pointed the audience to specific books and resources and concluded with examples of citizen science being used in a community context, such as the Covid Translate Project, and the last slide asked: Could citizen science – or something similar, with similar tools, methodologies or practices – be useful in your community? We hope a few audience members said yes.